|

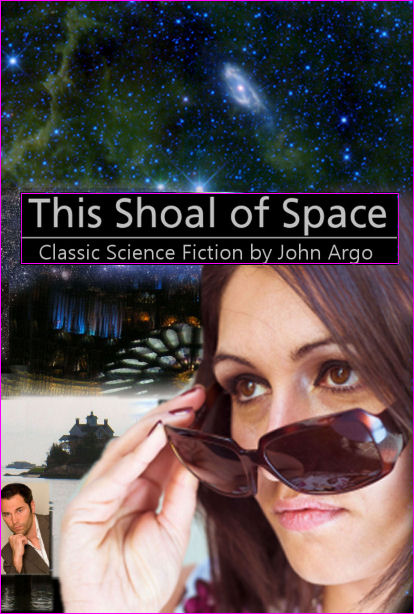

This Shoal of Space:

Zoë Calla & the Dark Starship

(World's First E-Book—Published On the Web in 1996 For Digital Download)

a Dark SF novel originally titled Heartbreaker

by John Argo

Preface

Chapter 1

Intralog

Part I-Chapter 2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

Part II-Chapter 66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

Outlog

Chapter 69.

Dr. Isaac Boutros, Max's doctor of old, showed up quickly at the E.R. He'd been on rounds right there in the hospital and he could only stay a minute. His eyes reflected worry and kindness as he pumped her hands gently. "You'll see, ZoŽ. Everything will turn out okay. You must hope and pray. I am ordering all the necessary tests now and I will return to see you later."

ZoŽ did pray, and sob, at the same time. Sister St. Cyr left around noon, promising Father Drinnan would mention Max during Dispensations at his evening Mass at state prison. He would ask the prisoners to pray for Max. Sister Sincere held ZoŽ's hands in a tight grip, and whispered in a flurry of words: "Their prayers can be very powerful if from the heart. Jesus loves the sinners, the hopeless, the lost. He has little time for the arrogant Pharisee, but loves the humble Publican. He is closest with murderers, and the lowest of criminals, those suffering at the depths under the shadow of prison bars, and those in the extremities of mortal illness. The souls of those in despair have the highest range to soar. He loved the Samaritan woman at the well, whom all others rejected, and he saved the criminals crucified on either side of him before any others." She pressed the black rosary into ZoŽ's hand before she left. "You know you are special to Him."

ZoŽ held Max's hand under the white tents in the emergency room. He felt warm to her. She called a nurse, and Max's temperature proved to be 101. God let it be flu. Please...

"I'm not real scared just now," Max told her.

"I'm not either," she lied. "Maybe just a little. Not a lot, though."

"Me neither," he said. "Not a whole lot. Just a little."

Before the bone could be set, Max had to go through X-Ray. There, in a semidark of quiet procedure and dull, careful routine, plates slammed through the huge machines as exposures were taken. Next, blood tests. Max went through all the needle sticks with a stoic face. Partly, she thought, it was because he was already doped up. She remembered the cancer years, and felt strangely detached. This wasn't the little five year old who'd suffered through all of that. And this wasn't his young mother and ex-convict caroming from cushion to cushion of life. Those two had triumphed. They had walked out of this fucking place hand in hand and chins up. This was a whole new ball game. This was a ten year old, and his worried thirtyish mother. Only the Doctor was the same (Boutros, Egyptian, Coptic, best bone man on the West Coast, a Burtongale catch. Thanks, Miss Polly. No, thank Wallace, who sponsored the State University football team).

Then came the specialists. They nodded, they conferred, they pointed to X-rays, they made gestures, they walked away and came back. They sipped coffee and nodded some more. They generally avoided looking in ZoŽ's direction; perhaps (oh I'm kidding myself) they don't know I'm sitting here around the corner in a cold draft wishing it was all a joke and we could go home now.

Max was in the cast room. He'd had his leg set and now the cast man was wrapping the fiberglass into place.

Dr. Boutros came and sat next to her. "ZoŽ, there is a tumor in his right tibia. That's the thin little hard bone you feel below your knee to your ankle."

She remembered every bone. "Is he going to die?" she asked.

"We have to take the leg off."

"He loves to play basketball," she said. She felt dull and saggy.

"ZoŽ," he whisked in his little accent, and she studied the crisp white hairs around his gold eyeglass frames, the caring brown eyes behind thick lenses, the soft cocoa skin furrowed with a thousand horrors and worries, "we have won the fight once before, together, and we are going to win it again now. Got that?"

She nodded.

"He will play again. Look at the bright side. People run and play on the new bouncy artificial limbs. And he'll never need crutches again. You should go get something to eat," he said. "It's six o'clock." What? How could that be? But he was right. The hospital corridors glowed snow-blind with too many fluorescent lights. Evening shift people trundled about in surgical gowns. She went to the cafeteria and forced herself to eat half a burger and some fries, not tasting anything. A middle aged man with a cigarette in one hand and a similar burger in the other hand was wolfing away; why not him? she asked, why not that guy? Why my Max and not some other kid? Why any kid? Why, God? We pray and pray and what do we get? She sniffled.

"ZoŽ." She turned. Roger, Elisa, and Rudy walked in. Roger sent the kids to get trays and order in the line (which was virtually empty because dinner was over but the cafeteria wasn't closed yet). He squeezed her hands. "I'm sorry."

"We beat it once," she said. "Why is it back?" He started to say something. She bawled. He slid around and sat beside her. He held her close and rocked her. Elisa and Rudy sat quietly.

"Let's all go up to see him," Roger suggested.

The charge nurse dictated hospital rules: Two visitors per patient at a time in the rooms, or five in the guest room. So they sat together with a huge Mexican-American family. Max, Rudy, and Elisa put their heads together for a serious powwow that made ZoŽ curious. "What are you gabbing about?" she prodded them.

"Just, um, about our rooms," Elisa said. "We want Max to get home soon." ZoŽ sensed something awry. But she checked Max's reaction, and he nodded as Elisa spoke.

"Well it's nice to know you're wanted at a time like this," ZoŽ heard herself blather. Roger held her hand, and she thought, last time I didn't have that either.

She sent Roger and the kids home about seven. Max had some pain and she got the nurse to give him codeine, which put him right out. He was in the pediatric section, so it was okay for her to spend the night. An LVN brought a cot, which was placed right next to Max's bed for her. She lay down to rest, planning to get up, shower, comb her hair, maybe drive home and pick up some clothes, but she fell hard asleep.

She had horrid dreams about dead people. Father Lawrence, wearing his long black soutane, stood someplace under water on a metal beam. He waved his arms and his face flexed in driven expressions. His eyes looked desperate. The metal beam on which he stood was torn off at one end, melted like a bar of sealing wax thrust into fire. Wiz stood darkly shaking her head. Like, no, don't something, but what? Grave men in bright garments woven of gray light, like angels neither good nor bad, or maybe both, were carrying a stretcher deep into a wall, through a doorway without exit, and when she looked closely, it was Max on the stretcher. Somewhere nearby was an airplane with all its lights on—but fish swam in and out of the cockpit windows.

A hand shook ZoŽ. It was the nurse. She had a tray of food for Max, in case he wanted to eat. She rose groggily, shaking her head. Max was still lying on one side. ZoŽ bent over him anxiously. He was still breathing. She pulled the cover up to his chin. The nurse said: "Doctor Boutros is on the floor. He asked to see you in the corridor."

ZoŽ found him in a nook between a palm and a picture, reading over some procedure sheets. When he saw her, he put the papers away and looked grave. "ZoŽ, we were calling you at home this morning. I'm afraid I have more bad news. The lab found some suspicious white blood cells. I had the radiologist go back and check the x-rays again. I am indefinitely postponing the amputation. We think there may be more tumors."

"NO..." She sagged against the wall.

"I'm sorry," he said. "I think we have to be very tough just now. We will do more tests, and right now it's not conclusive. But there is a sixty per cent chance that there is a small tumor in the other leg, and also one on the hip right near the kidney. And what that means is that there may be the beginnings of metastasis. We have to know right away."

"Is he going to die?" she asked.

"That is in God's hands," he said. "He is a very, very sick boy."

ZoŽ called her mother.

"Oh hi," came the drawling, dawdly voice.

"Mother," ZoŽ cried, "Max's cancer is back."

"I think you should take him to the doctor then," Mother replied.

"Are you drunk?"

"I'm knitting," Mother said. "Would you like to join me?"

ZoŽ hung up and called Roger.

"Oh my God," he said. "I'll do whatever I can."

His words and his tone of voice, however well-intentioned, at that moment seemed to have a distance, a cold finality that enraged her.

"He's not dead yet, and I'm not going to let him die!" she screamed and slammed the phone down. Then she ran outside to get some air, pushing aside startled nurses and staring patients.

top

Copyright © 1990-1996-2014 by John Argo, Clocktower Books. All Rights Reserved.

|