|

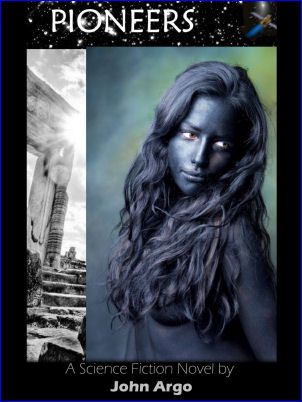

Pioneers

World's Third E-Book—Published On the Web in 1997 For Digital Download

an Empire of Time SF novel

by John Argo

Preface

Chapter 1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

38. New World—Year 3301

38. New World—Year 3301

Despite himself, he went the long way around, coming up on the post road where he'd last seen Tynan and Licia. Their camping spot was abandoned. Licia was gone. Gone with Tynan, back to Akha. That part of his life was over. He hid his meager baggage (sleeping bag,

shelter, rifle, pistol) and crept down toward the natives. He must see what it was they came here to do. There was another reason too, a hunger, that he could not voice. Maybe it was just the desire to be with people again, even if they weren't exactly people.

The tent city was cool with amber evening when Paul crept through the thick woods and underbrush. Lonely evening wind blew coolly around him in the high grass. He was hungry and realized he had forgotten to eat that day. The rich aromas of native cooking

permeated the air around the tent city.

The natives were in a celebratory mood. They ate and drank and sang boisterously. Drums rumbled across the valley as night fell. He watched hundreds of milling dark bodies from his vantage point. Still, new arrivals kept appearing amid rounds of warm, noisy applause.

Dozens of makeshift kilns blazed in the tent city. The twin moons shone brightly. No evidence of Licia or Tynan; he could be sure now that they had left for Akha.

He worked his way around the perimeter, ever afraid to be spotted. From the kiln area he heard piping and drumming. He could almost feel the thud of dancing feet. He heard the sharp breaths of straining dancers. Their laughter sounded as if it were all around him, and

he clung closer to the shadows.

At the downhill end of the tent city he came upon a scene of torches and hammering. He saw workmen drinking heavily, sweating and swearing around some indeterminate labor. In a corner of the work area was a pile of unopened flasks. Several men worked on a

wooden box big enough to hold several men standing up. Paul stared in puzzlement. An older man worked off to one side assisted by a younger man. The old man was white-haired and brawny—used to physical exertion all of his life. He hammered at an object while his slim, long-

haired assistant held extra tools and a brace of nails for him. The old man worked feverishly as if in a great hurry and resisted by the object of his labors. The assistant suggested something that Paul could not hear against the noise from the other workers. The old man shook his head

disparagingly at whatever the suggestion might have been. He uttered a command, and both men labored to lift the object on its side. Dull as he was by now from tiredness, Paul instantly recognized that he was looking at a wheel.

A wheel!

It was the first native-made wheel he had yet seen. He had thought that the wheel was a lost Avamishan art. Yet here it was—a thick wooden disk about three feet in diameter, reinforced with thick planks. The wheel stood on its side and the old man pounded more

stone nails into it in a hopeful but uncraftsmanlike fashion. Paul gaped. He was watching a group of stone age men building wooden wagon wheels. Why then had they not brought their heavy burden of stone wine jars to the tent city in wagons? Surely it made no sense to build wagons

after the work was done; unless something was going to happen here; something that had perhaps been commonplace in ancient Avamish?ĚPaul tried to think it through. After all, the natives had models for wagons buried all around their villages, only awaiting some renaissance. Was

there a Petrarch, a Leonardo, a SheuXe, a renaissance man waiting to appear among these people?

Paul stared at the drunken men who worked so hard at these tasks that had no place in their normal village lives.

Involuntarily, Paul peered up at the surrounding hillsides, but he detected no sign of one tiny, warm campfire. His sudden change of position still shocked him; he had to keep reminding himself that Licia was gone forever from his life.

One of the workmen stepped into darkness and Paul heard him urinate while humming to himself. Paul stole closer. He was thirsty, and those piled jars looked inviting. He stole two little ones. They felt cold and heavy, and they clinked unnervingly as he lifted them

from their mates. The singing and hammering covered whatever noise he made. He stole away.

He found a distant, high vantage point. There, he sat in misery and drank. Below him he watched the smoky, noisy gathering. The wine was sour-sweet and reminded him of Akha. For the first time, he wished he'd listened to both Tynan and Licia, and stayed in Akha.

Maybe she'd been right—they'd been safe there. What a fool he'd been. How he'd screwed up a mission that had taken a thousand years of time, 25 light-years of travel, and the last surviving six human lives. The apple wine smelled pungent. He drained the first jug quickly. The

wine gripped his unfed body as he pried the swollen cork out of the second stone vessel. He stared long and hard down into the tent village but could not find any trace of Ongka, Auska, Amda, even bumbling Dunda. Halfway through the second quart or so he rose with drunken resolve. He

would go down and announce himself to the natives. If they killed him right there, so what. He crawled and stumbled back downhill. It went quickly, and pretty soon he stood swaying, jug in hand, gathering up his courage.

Then he noticed a small wooden shack. The wood was freshly cut and planed, and held in place with a combination of wooden dowels, stone nails, and leather thongs. It was a neat piece of work. Instead of a door, it had flap of foul-smelling hide; probably fresh off some

hairy kill. It was unguarded. Paul staggered closer, set his jug down, and looked inside. Pitch black. Smelled awful. He felt about with one hand: lumpy, sour-smelling, hard objects. Round—no, cylindrical—he tugged one out and held it in his arms as if it were a baby. It was a

rocket about three feet long and two or three inches in diameter, with a long thin dowel for a guide. The rocket was packed in a stiff, resinous cloth sewn together at a seam running along its length, and covered with animal fat. So that was the rancid odor. Paul stood swaying in the

night, holding his rocket up to the unamused moons.

He laid the rocket back into the darkness amid its companions. Rocking back and forth on his heels, he lifted the wine jug and took a big draught. He rubbed his hands so that the grease came off onto his torn jumpsuit. The liquor coursed through his body like fire. He

felt hungry and wanted to go down into the tent city to get food. He wanted to drink and dance and make love with natives and Auska or someone like her. He staggered along the uneven, winding rim of the bowl of Avamish. He staggered for a long time and could not find his way. Finally,

he fell face-first into a bed of soft pine needles and passed out.

He was awakened by the sound of women laughing. His head hurt and he felt nauseous. The sun stood full over the horizon. The women's high, silly laughter sliced through his headache. A group of young girls played tag in the high grass and fragrant flowers, not far

down the hill. They were pretty children, naked and blue-brown, with sparkling eyes. Butterflies wandered about. He thought once more of turning himself in. Then he remembered the rockets, and decided he still had some exploring to do.

Oh, but his head hurt. He was famished and weak. He found a broken pipe from which fresh spring water trickled. He put his face to the stone and drank thirstily. Behind him, the girls and the women ran further down the slope, back into camp. He smelled food and

tracked down the remnants of their picnic—leaves, cold now, smeared with paste, beans stuck together, bits of bone and gristle, a scrap or two of meat—he was so hungry he devoured pieces of the leaves.

Near the space port, he shot a bounding rabbit-thing. He made a fire and cooked it. He peeled skin and fur off as it cooked, using his knife to bring the giblets to his mouth. The taste and sticky feel of blood brought him to his senses.

He remembered his lost canteen, and headed toward the park. He walked along the edge of a broad avenue. This was a new angle of approach, but all roads led to the star city. The avenue was carpeted with grass. Wind spirits blew loose brush around him. Wind whistled

in blank doorways and dark windows.

He crossed a line of trees and stood at the edge of a rectangular expanse big as an airfield. A number of small, low buildings were scattered far apart across the field. Beside each building stood a pillar of solid stone, broken off, the tallest about twenty feet high. Wind

soughed through with an empty, eerie effect. As he passed the buildings he looked into several. In one he found a wagon, broken in half, its wheels still attached.

In another building he found bits of petrified hay, along with a few scattered black stone bolts and wheel hoops. In a third building he found stone storage bins; they were empty, except for some broken cups.

All of the buildings were scarred and gouged, as if by bullets or crossbolts. Great violence had occurred here. There were signs of fire. Wooden doors had been bashed in.

In a fourth building Paul found a tangle of skeletons. They lay piled together and had mostly disintegrated. Each skull had been smashed by a heavy object—several times.

The climax of death was ages past. Wind blew remorselessly as Paul crossed the field. Perhaps this had been a market square—who could tell now?

He crossed a tangle of major avenues that led to various parts of the city.

He came, at last, to the place where he had left his canteen. He felt again the oppressive, sun-drunk park silence.

But the canteen was gone.

Someone or something had found it and carried it off. He cursed the statues that were poised as if converging on him. The giant philosopher head in the ground stared at him like an angry schoolmaster.

He yelled "Ongka!" and his voice carried no farther than the nearest tree, the nearest frozen discus thrower.

Near the exit he saw a small stone building he had not noticed the other time. Its walls were concrete, dark gray. The building was octagonal, worn with age, and had no windows. Its roof was intact, consisting of glossy greenish tiles that rose up, pagoda-style, at the

corners. All eight sides of the roof rose in the center, converging in a decorative black ball. For some reason, the building made him curious—perhaps literally, judging by the telepathic currents in this weird alien place. He walked around it and found the structure had a stone door

with a stone ring in a hinge. The door was closed. He tried the ring, and the door swung inward on silent, oiled hinges. Oiled? He knelt down and touched the threshold, then brought his fingers to his nose. No smell. No oil. Just well-built.

The door might have been closed a thousand years or more. Inside was darkness, dust, dry air. Not a single object—oh! his canteen lay on the concrete floor. Shocked at its migration, he picked it up. It had been nearly empty when he left it. Now it was full. Heavy.

He opened it and took a sniff. Fresh water, with a tinge of anise. He remembered the drug he'd been given his first day in Akha. Someone—Ongka?—had filled the canteen, moved it here—why? Why these stalkings, these indirect gestures? Just as indirect as when he

had been handed pick and shovel with instructions to dig into the mound.

He stared about him in the gloomy little room in which the only light was sunlight that crept through the open doorway. No furniture, no windows, just a barren room inside an eight-sided stone cylinder about twelve feet in diameter and some ten feet high.

Claustrophobic.

But wait! Paul suddenly realized that the walls, the roof, all but the floor, were completely sheathed in metal, in dully pitted copper. He touched the wall briefly. A strong thought ballooned in his mind: "Avamish..." said a young male voice lovingly.

Paul barely noticed that slowly, the door swung shut.

Remembering the thought-squares covering the wall in that dark bank vault, home of lizards, he closed his eyes (it was pitch dark now anyway), steeled himself, and placed both hands flat against the wall. The blast of sights and sounds and smells was immediate and

overwhelming.

top

Copyright © 1990-1996-2014 by John Argo, Clocktower Books. All Rights Reserved.

|