|

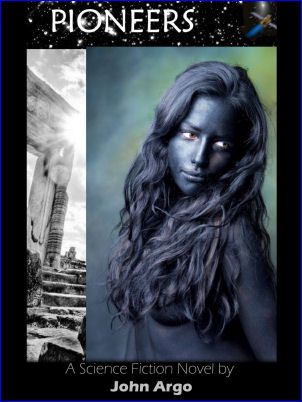

Pioneers

World's Third E-Book—Published On the Web in 1997 For Digital Download

an Empire of Time SF novel

by John Argo

Preface

Chapter 1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

40. New World—Year 3301

40. New World—Year 3301

When he recovered from explosion and the noise, Paul stared at the haunted evening park. He saw spots before his eyes. The statues shimmered mesmerically in a red flickering light. Two of them had beards. Had they been here before? They smiled enigmatically,

looking toward the star port with blind marble eyes. Paul suddenly became frantic to rush out of here, back to the wide, wind-blown avenues with their bowed grass.

He ran aimlessly. It was good to run. The night was like cobwebs, warm to brush through. Back to the sack, his mind said, back to the pack, to the back pack ... and his feet pounded on crumbling concrete. There was only one place left to run to, and that was the tent

city.

Several times the bellowing sounded, and each time he staggered, holding his ears. The noise was so loud that he was blinded for a few seconds, seeing shapes like black marble sliding before his tortured senses.

A second explosion: the ground shook behind him and lights flashed, briefly teasing daylight back into the night.

Another explosion rocked the ground as he ran up the hill. At last he presented himself in the native camp. Breathlessly bent over with his hands resting on his knees, he half expected to be killed. To his surprise, he was ignored.

Celebrants thronged the post road. The great festival had begun. Paul joined them not knowing what would happen next. Hands were laid on his shoulders and he found himself swept along. It was good to be among people again, good to eat kiln food. An answer was

shaping in his mind, but still full of holes, holes that must be filled with information.

There was a flash of light down in the city. It came from the launch center. The ground trembled as a huge fiery object lifted off into the atmosphere.

The natives screamed with delight and terror. Countless arms waved in the night tracing the rocket's course as it rose up over the city and the sea. It disappeared into the heavens, high up, among some clouds.

Each time the bellowing sounded, the natives would cheer and raise their bottles.

Paul started to run down into the city. He ran through the crowds of natives, pushing them gently out of the way. He must know about Avamish, now or never. Behind him he heard warning shouts. He saw dozens of torches flare up in all directions. Then, hearing

screams and feeling a rumbling under his feet, he jumped out of the way just in time as a dozen drunken, jug-holding men weaved down the steep incline sitting in a wooden wagon. In their uncomprehending way, they were trying to reenact the daily life of the ancient city! He heard the

scraping of stone brakes. The cart rumbling past picked up speed. Paul's hair stood on end as he realized they were getting more wagons ready to race down the hill. In each wagon were men holding a torch in one hand and wine in the other. One of the wagons caught fire and crashed

into some boulders and lay smoldering while its occupants dragged themselves to safety. Men and women waving torches chased the wagons on foot. They cheered loudly—a foot race, as it turned out, to see who would be first in towing the carts back up for the next run.

No time for this, Paul thought. He hurried down the hillside away from the road. He stumbled and slithered over piles of round objects that blanketed the hillsides. At first he thought they were skulls. Then he realized that they were empty amphorae. Many were old and

mossy. Some lay burst open like stone flowers; grass grew in their guts. "My God," Paul thought with a flash of insight: "How many ages and ages have they been doing this?"

He ran breathlessly through side street after side street until he could see the outlines of the space center clearly in double moonlight.

The ground shook again. A blast of heat hit his face. Thunder followed immediately afterward, penetrating his ears with deafening force.

He heard the bellowing, and this time was too amazed to sense the pain in his ears. As the bellowing smashed through the air, a column of steam issued up, thousands of feet high, from the center of the space port. It wasn't a dinosaur, wasn't some beast, but an artifact

of Avamishan manufacture. A siren, calling the natives from all over the planet. Telling them it was time for the festival. Moniam bestibo, he pictured Auska's sweet, wry mouth saying.

Behind him on the hillside he heard frantic cheering.

Another spaceship rose out of the rolling smoke, hovered for several seconds, then streaked away to disappear over the sea.

Not good to be here. Smoke filled the air, and he coughed. His lungs hurt as he forced himself to get closer.

The siren bellowed again, no doubt stirring up birds hundreds of miles away and scaring the whales in the deep sea.

Behind him on the hillside he heard frantic cheering.

Another space ship rose out of the rolling smoke, hovering for several seconds, then streaking away, disappearing over the sea.

Paul's lungs hurt as he forced himself to get closer.

A third rocket went up as he approached the star center. The ground rolled in waves. He fell to his knees but got up and continued running. He smelled acrid smoke. A number of outlying bushes and trees had begun to burn brightly. The air was hot and searing. There

was a rumbling in the earth as yet another space craft was made ready for flight. Paul shielded his eyes, striving toward a nest of tiny lights he saw twinkling in the interior of the lizard-infested launch buildings.

The sprawl of grass-covered launch pads flickered with flames falling from the launches. As he got closer, he passed the building that seemed to stand on its fingers. The water in its pools was lit from deep within, murky bottle-green, but bright enough to see the

hammerhead sharks circling frantically, their twin catamaran bodies whipping this way and that in terror. Paul saw again the sunken rocket bodies, only in this light it was clear they were covered with barnacles and weren't really made of metal, but of stone.

He came to a narrow stairway. At the bottom was a half-open door, and light spilled out. Down he went, where it was cooler and the air clearer. He found himself in a long dry corridor lit by rows of tiny gas lights along the walls.

His feet echoed on the floor as he ran, closer to the heart of the mystery.

He came to a door of stone bars—open. And another door, also open. He heard a thumping sound, a steady rhythm like that of a room full of washing machines. The light here was a weak pinkish-yellow that he remembered from the deep Aerie—fungals, that

could last virtually forever. He ran one finger along the purple wall, leaving a wavering smear. He smelled his fingertip and gagged; dry smell of mushroom earth. The corridor turned into stairs again, sloping downward, curving to the left and then the right. The machine noise grew

louder, the air warmer, thicker, so that he almost wanted to hold his ears.

As he continued descending, there was a sudden change. The light merged from sickly pink into insect amber and then into iodine blue. The walls turned mauve, then reddish blue. The light-giving fungus became patchy, and the surfaces around him were not stone but

metal. He touched the ancient brassy surfaces, running his fingertips through the pits and corrosions that had occurred over the ages. The surfaces curved gently emerging from rock and losing themselves again in rock. He smelled something—food, he thought. The kilns. How

homey. How human. But there were other whiffs and smells and stinks in the air—sulfur, iodine, methane. A factory, Paul thought, listening to the relentless machinery that sounded almost like a human heartbeat.

He heard the piercing cry of an animal larger than the zeppelin whales.

It was a whistle from an organ pipe throat, a bellow at the stars.

Down here in these primordial corridors, he saw the images of the long-dead spacefarers. They had loved to make pictures of themselves. They looked not quite like Earth people, and not quite like Avamishans. Some looked a bit like Hindu gods, with red faces and extra

arms; others looked more Chinese, perhaps, round and smothered in their wrappings, with happy laughter at some enigmatic situation of 10,000 or 100,000 years ago. Whoever they had been, they were so long ago that they made the ancientness of this dead city a matter of yesterday, of

an hour ago, by comparison.

Paul ran on. Free, a citizen of the galaxy, he jogged without fear down the stone and metal corridors. The fungal lighting gently guided him. Its violet glow made the smooth stone floors seem carpeted with photons. Firefly insects swarmed like passing stars, and he

brushed through their humming nebulas. The spattered his face coolly, like fresh water. He caught a whiff of anise. On a hunch, he touched the wall and tasted what was on his fingertip. It was the same thing he'd drunk that first day in the village. Not an herb picked from their gardens,

but a substance that grew here in the heart of Avamish. He laughed, wiping the condensation from his face, feeling clockwork knowledge boiling up omnipotently in the unused chambers of his brain.

He followed the smells of cooking and the thumping grew closer and louder. The light changed again, more into amber, and then into sallow yellow like the cooler part of a burning sulfur match. The corridor was crossed by other corridors, and they all ran to a mezzanine

of stone and metal overlooking a great gallery. He arrived at the parapet (a wrought iron thing, made, not begotten, full of chaos, no two hoops or squares repeating the same pattern) and leaned on it, catching his breath, trying to make sense of what he saw.

First he was confounded by machines that hung in the air. They were the source of the lumpa-thumpa sound. Brittle old wheezing gadgets, weeping steam, shaking as they pumped air down to the factory floor through leaky leather hoses.

Figures moved everywhere down there, completely covered in light, loose-fitting suits. They were natives, Paul felt sure, each also wearing a kind of glass helmet. The helmets were opaque, colored almost like tarnished copper, but with clear face areas. Each hose ran

down to the top of a helmet; no helmet without its hose. What could it mean?

Though the ceiling above was pitch-black, fading upward and lost in stone vaults, the light in the gallery itself was a pleasant citron, like flower petals glimpsed through a wet shower door of wavy glass. As Paul learned to ignore the noisy machines that hung in the air

before him, he was able to make more sense of the scene below.

The floor of the gallery was regular, manufactured, not natural. Probably metal, blackened with age, but shiny, coppery, where generations of feet trod in ritual motions. The floor was roughly oval, about 500 feet from long end to long end, maybe half as wide, just big

enough not to be claustrophobic. Scattered across the floor were tables, work benches, shelves, machines, conveyor belts, stone rollers. Moving down the rollers were big composite tubes, paper-thin metal/stone alloy, like the sunken rocket body that was home to catamaran sharks. Men

and women mixed the fuel together—nitrogen dioxide probably, fertilizer, cousin of nitroglycerin—and sewed it in membranes. The sausage shapes moved down their own conveyors, joining the rocket bodies, packed, loaded, sealed, and ready for the next step. Paul gazed toward

the far end of this strange cathedral and saw men without helmets—they were about 20 feet higher than floor level, and about 20 feet below Paul's eye level—hoist a finished rocket into a standing position atop a shallow platform, a kind of triangular recess or corner.

Already, the fierce bellowing of the siren cut through the atmosphere. He understood now—it was a release of volcanic steam, the same steam that had powered factories like the foundry they'd found near the river gorge. The ancient Avamishans of a thousand

years ago had unlimited power.

The rocket on its pedestal was a slim cylinder about thirty feet high, with a cone shaped nose, and small fins at the bottom end. The men jumped down from the platform. Paul watched at the platform began to turn. It was a kiosk, sort of like those revolving doors he'd

heard of in ancient hotels. The platform turned slowly, and the rocket rotated out of sight around a corner, while a new empty niche appeared. Already a new rocket was almost ready to lift onto this platform. Production was in high gear, evidently; Paul wondered how many days the

festival—moniam bestibo, he fondly recalled Auska saying—lasted; probably until they ran out of rocket fuel. Or rockets.

There was a tremendous growl from the other side of the mountain as the rocket caught fire. The chamber was sealed tight, and no exhaust gases leaked in. It had taken thousands of years to get this production line perfected, Paul thought. He could picture the rocket,

sitting in its launch tube, at first immobile, then bathed in an increasingly intense plasma of burning fuel, and finally propelled screaming into the atmosphere—to where? Moon I? Moon II? The whales across the horizon? From the night city into the day sea on the other side of the

world?

Probably nitrogen atmosphere down there, he figured. Minimize corrosion, explosion danger. They had these old machines that pumped a constant supply of breathable air into their helmets, expelling the old air, which then floated away in the bath of nitrogen gas. Had to

keep refreshing the air, not just to breathe, but to prevent nitrogen sickness.

Paul became aware of the figures surrounding him. His head swam with the anise drug as he turned, arms swaying drunkenly, to survey the circle of dark figures wearing round copper disks. He tried to talk, but no words came out. Words were not necessary. He could

feel them gathering their thoughts, for they were about to think with him.

As he sank to his knees, arms grasped him at the elbows to steady him. He recognized Amda, Ongka, the shaman from Shka, but there were many others he did not know. They led him down a long narrow corridor of brightly twinkling tile walls lit by gas lights like the

ones they had found in the way station on their way to Shka. The tiles were white, the lights strangely match-like, blue at their hottest, then yellow, fading into tall red cones.

They took him to a dark room containing what looked like a doctor's examining couch and a table. On the table lay several items he recognized, including the control panel the hunters had brought home to Akha that early night. They helped him onto the leather surface

of the examining table and draped a sheet over him for warmth. Still, he shivered. The drug made you sick. He thought he must be feverish. Then he felt sweat break out on his forehead. He felt female hands, gentle, with a sponge. Warm clear water. He looked up. Auska. She gazed into

his eyes with concern. She wore a copper disk.

The medicus men gathered around the table. Each laid a hand on Paul. They all stared into his face, and he involuntarily found himself relaxing, opening up like a pool of water, from opaque to translucent to transparent. He became a rocket body and his struggling

thoughts were catamaran sharks as they dove into the pools of who he was.

He felt again the spell of Ongka's mind, only this time it was magnified by the power of several minds acting upon his own. He managed to croak in a dry voice: "Why?" Now, at last, the time had come for a meeting between Earth and Avamish. It was time to find out why.

Why all this? Why the Senders, when their city stood empty. What future for the people of both worlds?

The magic of the eight or more glittering metal disks drove away all shame, all privacy, all secrets, even the mysteries he kept from himself. The disks were ranged in a circle over him. Faces peered at him from over the disks.

A mind reached down to touch his, gently; it was Ongka. "Hello, friend."

Fearlessly, Paul stared back. All the walls were gone and Ongka probed Paul's mind while Paul found himself, for the first time, at liberty to explore the shaman's thoughts. He found power, but more, he found fear and confusion and he could not say why. But there were

also warmth, concern; more than anything, a desperate hope. He recognized the yearning of murmur and singing from his balloon flight in the octagonal chamber in the park. "Oh Avamish!" cried a young girl. "Avamish, our Avamish," sang a choir of robust male voice rising amid organ

music.

Paul was surrounded by a wall of minds. Each mind was a cell. Each was separate territory but interlocked with all of the others. Their combined power mastered him completely and yet it was a delicate, gentle power, surgical in its skill to dissect without destroying. And

Paul felt a new power of his own. He could not master his own telepathic process, but stern, friendly minds helped him to project: what? "What is the nature of you?"

The greatest of them was a medicus from Avamish itself, named Dauli, and now Dauli took charge. The other minds stepped back and Dauli's simple, clear, razor-sharp thoughts entered Paul. In Dauli, Paul read the terrible truth, and he wanted to cry. He felt an

overwhelming horror at his own mortality. He felt the horror of man's vertigo on the brink of the eternity of time and space. He saw the meaning, the summing-up, of Avamish now that nearly everything possible was said and done and after three thousand years since the founding of the

city the end of Avamish was near. No, that had already happened long ago. Another thousand years had passed. Time meant nothing to Avamish.

Dauli let out a great, ironic mental laugh. He imprinted on Paul a sense of what it was to be Avamishan: he demonstrated the power and glory of his birthright. With deadly playfulness he took Paul completely into his power. Paul's soul was lifted kicking and screaming

out of its physical context. Dauli laughingly threw him into free fall spinning and glittering with wet reds and grays and whites. Dauli's mental power was like that of a master of the martial arts, smooth and practiced and undefeatable.

Paul's entire nervous system was like one exposed nerve. He was tossed and tumbled terrifyingly through caverns and passages while Dauli examined minutely the very essence of what Terran Man was all about. Not a miserable detail of Paul's racial memory was left

untouched everything came into play... :*:*: Gregory, SheuXe, Aeries:*:*:New York, Sumer, Akkad:*:*:Egypt, Rome, NASA, UNASA, CANUSAMEX:*:*: the clouds:*:*:...

Fear raised its slithering saurian tongues. Terror clashed its foamy teeth. Horror's glazed, wide eyes stared. Hatred's insane eyes bored down on Paul with a sound like that of a pin slowly grinding its way through a struggling beetle... :*:*:...Paul soared howling and

thrashing through a black lightless void at the pit of which Death's putrescent worms squirmed and tangled like tripe... :*:*:... :*:*...He stood helplessly atop a ruined wall overgrown with grass and weeds. Beside him stood Dauli and Ongka and Amda. They pointed toward the post road

leading away from Avamish. Two figures walked there, Tynan and Licia. Tynan slid his arm down her back and caressed the curve of her rear. She reached up with both arms and pulled his head close to hers for a passionate kiss... :*:*:...The truth, Dauli lasered into Paul's soul, the

truth!

Paul emerged in a place even more terrible... :*:*:..Loneliness. His momentum left him sliding over a plain of ice where frozen stalactites jutted up through gravely-abrasive snow crystals. He stared at a starless, moonless blue-black sky in which the last stars had died of

cold. He saw the empty shell of a ruined Aerie imprisoned for eternity in an icy cobweb...its empty black windows stared upon him like skull eyes, asking, accusing...*:*:...

But then...

...J+O+Y+O+U+S W+A+R+M+T+H showered him with relief. More than an explorer, Dauli made things he found wrong right and good again with the delicate hands of a master technician. Paul rejoiced reaching for a warm breast and its milk was sweet as hay, fresh as

beach towels in mother's closet for going to the sandy lake under glass ceilings in the Aerie. Blood rained through Paul in a yellow and red shower that fed every cranny and every corpuscle and was full of light, X-rayed with Mediterranean sunshine (oh gone Earth! Oh Earth, my Earth!),

each droplet of blood becoming a rainbow wheel of stained glass...and together all the rainbow wheels made a mosaic of infinite dazzling choruses of light...

"Avamish," said a man from one or two thousand years ago. "Oh Avamish," a woman answered. Paul heard lute music, the tinkle of cymbals, the rubbing clatter of a sistrum, as a boy's reedy voice recited poetry in sussurant classical Avamishan. Crystal goblets tinkled

around a table and Paul felt himself toasting a new bride, who bore one nipple exposed and was beautiful as a Polynesian sunset. She was the young girl from the tomb of the ascending rockets. He heard the thunder of rockets as a space ship thundered and blazed up into the night sky.

Paul could not remember if that would be the troop ship to Orion or the botanic barge for Eridani or the evening luxury passenger liner to Fomalhaut or the mail run to Altair...

Dauli tore the fabric of illusions away from Paul's dazzled eyes like a conjurer unconjuring. Paul looked at Dauli hurt and resentful. Twelve minds caressed him slowly back to the white-noise level of consciousness. Slowly the opiate of illusion yielded the truth, the

bittersweet truth of what Avamish and Earth might both have been but were never able to become.

Just as Earth had perished in its clouds, so Avamish was a dream of what never had been. Every year, the natives still came to revel in a fool's religion, an impossible dream. They came because their ancestors had also come each year to marvel at the city of

dreams.

There had, in truth, never been a city of the stars. There had never been an empire or space flight or a single moon base. All of Avamish had been a wonderful story, a celebration, a continuous drama whose actors were the entire population of the world. The planet

lacked metals and there was no escape from its gravity. No need for a city or a star port. The land and climate were good and society was agrarian. But the spirit was not satisfied with peace and plenty. Over the centuries, a technology of stone developed and was refined to untold heights.

Science, philosophy, art, these had no physical boundaries. Avamish had its own Newton, its Aristotle, its Gauss, its Einstein, its SheuXe. The philosophers and engineers built a great city and called it Avamish, which meant Our Journey. Still not satisfied (why be?) Avamish had looked

to the stars. But it could not reach them. Especially tantalizing was the fact that Moon II was practically made of iron. Just out of reach, sorry.

At the height of its splendor, Avamish was an industrialized society comparable in many ways to Europe in the late 1800's. Stone and wooden ships patrolled the seas, fishing and trading. Zeppelins plied the air. Steam-powered trucks and buses traversed a network of

post roads covering both continents of the planet. All roads led to Avamish.

Where physical progress left off due to the lack of metals, spiritual longing kept on. The thirst for star flight was unquenchable. On Earth, the dreams of fantasists led to technological realities. On N60A, the dreams continued and were never more than dreams. A pseudo

space technology complete with would-be engineers, astronauts, bureaucrats, politicians, clerks, and manual laborers came into existence. All the world came to see and be part of the dream, the drama, of what could have been. Of what was promised would one day be reality. It became a

religion. But the seeds of undoing existed in a false dawn, the flowering of unreality as reality. Avamish was a hope without substance or fulfillment. Convolution and involution brought disease to her arts and sciences. Light, graceful architecture yielded to buildings and statues of

gargantuan proportion and clumsy balance. Elephantism set in. Exhaustion followed soon after.

The city became a tired dream that taxed the entire planet. Eventually the country mice rebelled against the city mice. A coalition of farmers and slaves stormed the city and burned it, killing all its inhabitants except a few who hid in secret underground passages.

These kept the dream alive. The wonder of Avamish remained as a sort of afterglow. Technology was sealed into mounds, put back into the embrace of the earth, forbidden. In time, enmities were forgotten. The taller, lighter Avamishans with silvery hair, like Auska, reconciled with the

darker, shorter ones of the spinal manes and bald heads. The warriors who had sacked and burned Avamish had borne, painted on their faces and over their heads, a white stripe symbolizing the simple village gods of the wheat, the kiln, the orchards that brought forth apples and heady

liquor.

Still today, having long forgotten the nature of the city, the natives made a regular pilgrimage of meat and wine. Each time, Dauli and his native technicians put on a great show for them. Amda and his youthful companions were the next generation of medicuses in

training.

Paul, floating in this bath of information, this white nowhere, felt Dauli nudging him, mind to mind. There was more. To really understand the nature of Earth, of Avamish, he had to look deeply again. Deeper than before. Deeper.

There he saw it. The ancient spaceship. Crashed. Dauli showed him a picture: Black outer space spattered with stars. Ships. Ancient ships. They had been to Earth, to Avamish, to a million other points. Time meant nothing to them, these ancient people who had left

settlers on a million primitive but lovely gardens of Eden. They were indirectly, by default, in a sense the real Senders. They had conquered time and space. They had only not conquered themselves, for that was a fundamental law of the universe. All things that are born must grow old

and die. Stars, planets, living things, all are bound by the natural processes. The ship, Dauli said, stayed behind when the Ancient Ones disappeared. (Where are they now?) We do not know. They may have died out. They may come again tomorrow. They travel through time as readily as

they travel through space. They visited earth during your Ice Ages. (How do you know this?). The metal of the ship conducts thought. We make our disks from it.

Paul got a picture of woolly mammoths crossing an ice sheet, pursued by bearded hunters with pale skin and head hair. He recognized the constellations undistorted not by distance from Earth but by distance backward in time.

You see, Po-wul, we are of the same people.

(I had begun to think so). Paul wondered how much of this SheuXe had known or guessed, that sly old fox with his master plan.

The genetic material is plastic. It drifts in the soup of its own stochastic processes. It reacts to outside influences—radiation, starlight, heat, anything that can alter the genome. I am tired now, Powul. We have much to do together. You come, you bring hope. You

will be a great medicus here. You will bring your people—

—Paul had a picture of Tynan and Licia walking away, he fondling her, she reaching up to kiss him—

—together because you have more wisdom than the rest of them. We will protect you, because you are like us. You are we. We are you. We have failed here and you have failed there, but the very fact that you reached us here means there is hope. You have brought

us a great news and a great joy, Po-wul. Thank you.

Dauli held up a shiny copper disk on a leather thong and, with great dignity, laid it on Paul's chest. Then Dauli withdrew. Paul began to feel the hypnotic spell lift. He longed to sit up and put the disk around his neck. No longer alone. No longer despoused. No longer

nothing. And still a citizen of the galaxy. For they'd owned the stars once, and they would do so again.

Ongka approached. "Now you understand, Po-wul. Touch my disk and look once more into my mind." Paul did so; saw again the clockwork. Ongka smiled. His range was fractional compared with the vastness of Dauli's. Ongka was no more than a technician. Paul saw an

image of Ongka sweating as he worked on the innards of a thousand-year-old stone rocket guidance system by gaslight in the underground rooms of the space center. After the rockets were launched, they briefly-illuminated the entire city and eclipsed the night. Then they flew out to

sea, to a very specific region where Ongka directed them. A year later, when the celebration was to begin anew, the tides would bring back the spent, green-garlanded, barnacle-crusted rocket bodies. Then, feverishly, the technicians worked to restore the rockets for the celebration.

As the hypnosis faded, Paul realized sadly that Dauli himself comprehended almost nothing of the city's vast blueprint of titanic stone machinery powered by the wind, the sun, and the hydraulic forces of the tides. The vision contained in Dauli came from telepathic

sources buried within the ancient spaceship, whose floor now served as the assembly point for fantasy rockets. Each technician had a metal disk on which were imprinted telepathic instructions on how to accomplish a specific job. No wonder that a stone age man like Ongka could know

the order of the heavens or how to repair a rocket guidance system, without actually understanding astronomy or physics or engineering. No wonder they had not really bothered to dig out the mounds or to rediscover the wheel. The mounds were their collective bad memory of the last

days of Avamish. To open them would be to confront the dead buried there, butchered during the worst of the rioting and warfare, when science had become reviled and feared.

The ground thundered as Paul drifted off to sleep, and another of Dauli's rockets sought its target in the gray, churning, fishy night sea.

top

Copyright © 1990-1996-2014 by John Argo, Clocktower Books. All Rights Reserved.

|